ABOVE: A Norwegian sniper with the Barrett MRAD .338 caliber. Simen Rudi/Norwegian Defence Materiel Agency (NDMA)

Designated Marksmen and Snipers

An infantry squad has traditionally had one man with a special role—to take out enemy targets at ranges up to 500 to 600 meters. He is the squad’s designated marksman, also called a “sharpshooter.” Designated marksmen are trained in quick and precise shooting and are expected to lay down accurate rapid fire at targets, extending the reach of the squad’s fire. He operates a rifle with a telescopic sight. The term sniper was used in the Soviet army for soldiers using a specifically designed rifle, the Dragunov SVD. A sniper is a specialized shooter who normally operates in a pair—shooter and spotter—or with a sniper team to maintain close visual contact with the enemy. Snipers shoot enemies from concealed positions or distances exceeding the detection capabilities of the enemy, and at a longer range than the squad’s designated marksman.

Lessons Learned

There is certainly something to learn from asymmetric warfare in Afghanistan, where U.S. forces and the International Security Assistance Force faced insurgents in vast open terrain and confined urban settings. The Taliban were adept at hiding themselves and their weapons, as well as blending into the local population. Since it was hard to differentiate the Taliban from the village’s general population, noncombatant civilians often became unwilling human shields.

The unique demands of this conflict environment had a major impact on the development and deployment of sniper equipment. A lot of lessons are learned in operations, including the distances in which the soldiers are engaging targets. Many Al-Qaeda and Taliban insurgents played hit-and-run tactics from mountain and ridgelines. The tactic was to deploy during the cover of night and be ready to ambush at first light.

It was difficult to estimate the range due to the terrain—many areas were so open and there was no reference point to use the mil-dot reticle formula to get distance. A need for a new sniper rifle with increased firing range was clearly identified when Norwegian soldiers were engaged in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. Shots from the enemy snipers firing from ranges around 800 meters were not exceptional. HK416 assault rifles with a caliber of 5.56mm were not capable of effectively firing against enemy targets at that range. The infantry squad marksman’s 7.62 x 51mm caliber HK417 rifle turned out to be somewhat short of range usually in Troops In Contact. The HK417 theoretically had the capacity to hit with accuracy at such ranges, but in practice a small or moving enemy at a distance of 800 meters is difficult to neutralize during a fire exchange. In many cases, the solution was to use the Barrett M107 .50 caliber (12.7mm) anti-materiel rifle. This became somewhat controversial when some nongovernment organizations claimed that using such a large caliber against personnel targets violates the Hague-Geneva Convention. Even though this discussion was soon extinguished, it was nevertheless a burden for the shooters to carry the Barrett up and down sand dunes and mountains. The signature of the weapon was also enormous—muzzle flash and bang generated airborne dust and debris. When the first shot was fired it was not wise to use the same firing position any longer.

Many NATO forces used the .338 caliber for some time with success. The .338 caliber’s range is approximately equal to a weapon in .50 calibers. A .338-caliber weapon with ammunition has a weight about half of a .50-caliber system. The .338-caliber bullet’s effect against personnel targets is impressive, even to ranges up to 2 kilometers. The experience using .338 caliber by NATO and Norwegian forces made it obvious that a new sniper rifle with a caliber between 7.62mm and 12.7mm would be the most appropriate solution.

A project group in the army, in cooperation with the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), started work to determine what sniper rifle system would be best. Capt. Alan Jensen, a master sniper instructor with the Norwegian armed forces from the Land Warfare Center, said, (in communications with this article’s author) “At start, one thing was determined; we should have the best weapon, the best ammunition and the best optics available. If necessary, things should be made from scratch.”

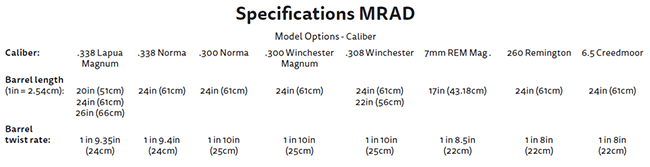

FFI’s first step was to identify what bullet type could achieve the desired effect, then which cartridge and powder type would give the bullet the right velocity and, finally, what weapon was suitable for that cartridge. After a somewhat ambitious start, the conclusion was that the .338 caliber Lapua Magnum 300 grain—optimized for the longest shots with the heaviest and highest BC bullet in its class—would be the most optimal solution to maximize the range and minimize the effects of field uncertainties such as wind and range. This conclusion was not only for operational reasons, but also for practical ones—this caliber was already in use by several nations.

Weapon Selection

Testing of weapons involves a number of challenges. One is finding precision rifles. All serious suppliers of such rifles have precision rifles with the quality necessary to achieve accuracy, but would those rifles have accuracy with the chosen cartridge? The .338 caliber was chosen before the rifle, not the opposite, as is often the case when choosing a new weapon system. Some of the weapons tested did not meet the accuracy requirement set for the chosen caliber.

The selected weapons became more difficult to distinguish from one another. The criteria depended on weight, size, ergonomics and technical solutions. Some outside the process questioned why one of the most widely used weapons that were combat-proven in war zones for longer periods weren’t chosen. They often used Accuracy International and the Sako TRG. Why gamble on something like a prototype or untested weapon system like the Barrett’s new Multi Role Adaptive Design (MRAD)? What might not be obvious to those questioners was that the actual rifles tested were not of the same standard as those that most other nations had in their inventory. The manufacturers had to modify some of their weapon components or solutions in order to meet the requirements for the weapons to be tested. These specifications were, at that time, not a standard with any manufacturer. It can be said that small design changes did not have a substantial influence on accuracy. However, the total result of the weapon’s weight, size, accessories, robustness and function under extreme cold and heat can make the most obvious weapon not good simply because the design or the technical aspects do not meet the demand. After a testing period with weapons, ammunition, accessories and optics, three candidates were selected. While all weapon systems were very good solutions, one was outstanding: the Barrett MRAD. One of the observations made during testing was that all shooters that used the MRAD for the first time obtained very good shot groupings. Not necessarily the best, but well within the set requirements proving the accuracy of the MRAD. With other rifles, the shooters had to go through some testing rounds before they obtained good shot groupings. One of the reasons may be that the MRAD is designed as a military weapon, using the well-known assault-rifle design as a model. Anyone who has operated an HK416, M16 or AR-15 will immediately feel acquainted with a MRAD. Because of the similarity to the M4 and M16’s pistol grip, the thumb-operated safety configured for right- and left-handed operation, the ambidextrous magazine release, the upper receiver with M1913-length rail space and the bottom rails for accessories, the overall design is recognizable to most Western soldiers who have had experience with the weapon’s system. That experience has created some muscle memory for operating the weapon’s controls and made the ergonomics feel familiar.

As Capt. Jensen put it, “If you have experience from the assault-rifle design, one can almost say that even if you never have fired an MRAD before, you will still feel that you have fired hundreds of thousands of rounds when shooting with it for the first time. In addition to the above, I think that one of MRAD’s success criteria is its slim profile. Barrel, upper receiver and stock provide a straight line towards the shoulder. That design results in a recoil with minimal jumps vertically and horizontally. This also makes it a very comfortable shooting weapon, especially when the signature damper is attached (other rifle designs where the buttstock is not in line with the barrel and upper receiver, tend to “jump” more during shooting). You also clearly experience its military DNA when you grip the MRAD on the handguard and pistol grip. My personal experience the first time I got hold of this weapon was that I’ve held this before. Unlike the other competitors as the new sniper rifle, which may have bulky hand guards and stocks, Barrett’s MRAD has a clean and a distinct military style. MRAD is not a competition or a hunting rifle; it’s designed for military use only. There is also nothing protruding on the weapon that conflict with the load-bearing equipment, tactical or ballistic vest the snipers normally are wearing. Typical protruding little things can be, for example, adjusting screws on the stock hooking up on the chest rig that has a variety of pouches and bags; or the magazine is unintentionally released because the magazine releaser is pressed against the belt buckle during carrying. That does not happen with the MRAD. It feels like a piece of equipment that enables the user to engage full capacity during combat. In addition, MRAD proved to be a very robust weapon. Even after several thousand rounds, there was no mechanical wear on parts that could indicate that this weapon had been fired with 100 or 2,000 rounds. The precision, range, ease of use and, not least of all, the psychological feeling of operating a weapon you know you can count on has made the MRAD a favorite of all of our shooters.”

Operational Use

The Barrett MRAD was introduced too late to be used by the regular Norwegian snipers’ involvement in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the Norway shooting community welcomed the weapon. After more than two years of use in the Norwegian armed forces, the MRAD, along with training and education, resulted in the Norwegian Telemark Battalion becoming the winners of the 2016 NATO sniper team competition. And, the Panserbataljonen (the Armored Battalion in Brigade North) had the best foreign team in the 2017 Danish international sniper competition, thanks to the sniper’s best tool and training.

Said Capt. Jensen: “The sharpshooters themselves refer to the weapon as ‘the laser rifle’ due to its unmatched accuracy and reliability. They know that if they miss the bull’s-eye, they cannot blame their MRAD! After being used throughout winter and spring conditions, there have been a few details that have had to be modified, something to expect when a new weapon system, for first time, is taken into use. But none of these have reduced the snipers’ enthusiasm for the weapon. It’s a weapon they proudly show off and always choose when the demands are greatest. The weapon’s capability has proved to work under all conditions. The technical solutions combined with the material quality have made this sniper rifle not just a solution for today’s needs, but also for the future. The MRAD’s design allows the rifle to be adapted to future needs and new requirements. This applies both to quick change of caliber and adding additional accessories that may be required.”

Barrett MRAD–Multi-Role Adaptive Design

The MRAD concept comes from an actual military program. They wanted a multi-role design, a multi-caliber rifle and an extended rail so they could mount thermal night vision and anything else in front of the sight along with a folding adjustable length stock and adjustable cheek piece. Multi-role means user-changeable caliber barrel system using the same chassis. Adaptive design means that it’s adjustable for anybody.

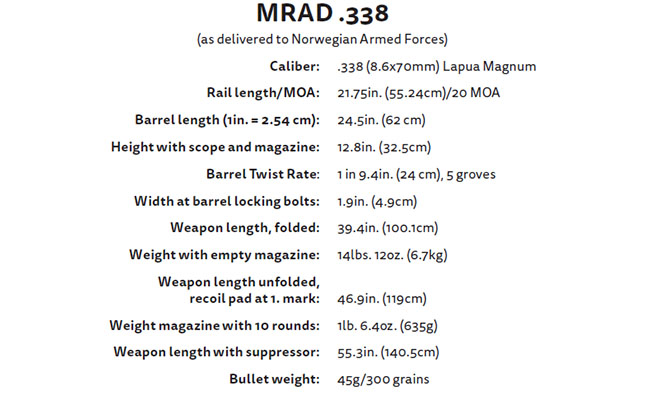

The MRAD delivered to the Norwegian armed forces has a precision-grade barrel that can be removed by simply unscrewing two bolts using a standard Torx wrench. The MRAD has Barrett’s new user-accessible, fully adjustable match-grade trigger module, which is drop fireproof and combat-ready. The safety can be configured on either side of the rifle. The ambidextrous magazine release can be used intuitively while retaining a firing grip and cheek weld. Integrated into the MRAD rifle’s 7000 series aluminum upper receiver is an M1913 with 20 MOA taper and 21.75 inches of rail space. This leaves plenty of room in front of the scope sight, on the side and bottom rails for accessories. The MRAD stock is foldable for enhanced portability and locks in as solid as a fixed-stock rifle, creating a rigid platform for consistent firing. The rifle’s length of pull can be set to five different positions with the push of a single button. During transport the stock folds and locks onto the bolt handle. The slender side-folder adds minimal bulk to the rifle, maintaining the same rifle width whether folded or extended. This rifle can be configured to the users’ requirements.

After a testing period with weapons, ammunition, accessories and optics, three candidates were selected. These weapon systems were very good solutions, but one was outstanding, the Barrett MRAD. The pictures are taken during some tests with the MRAD:

1) Lightweight folding stock with adjustable length, polymer cheek piece is height adjustable from either side, and ultra-absorbent Sorbothane recoil pad. Rear Picatinny rail for monopod installation.

(2) Mil-Spec Type 2. Class 3 hardcoat anodized Cerakote MRB, coyote tan/camouflage color.

(3) Polymer bolt guide acts as dust cover and provides smooth bolt cycling.

(4) Schmidt Bender 3-20×50 PMII.

(5) Integrated aluminum upper receiver has a 21.75in. M1913 rail with 20 MOA taper. The upper receiver is drilled and has accessory rails at the 3-, 6- and 9-o’clock positions.

Precision Weapon Portfolio Engagement Ranges & Dispersion

The U.S. Army hopes to field a new precision sniper rifle by fiscal 2021. The PSR is a multi-caliber rifle that will enable sniper teams to engage man-sized targets out to 1,500m. The PSR is supposed to replace the army’s M2010 sniper rifle, chambered for .300 Winchester Magnum, and the M107 sniper rifle, chambered for .50 caliber meaning to divest of two existing sniper rifles if this comes to fruition, the M2010 and the M107. Source: Military.com/Army Maps Out Future Small-Arms Programs.

The U.S. Army is also searching for a new 7.62mm rifle to become its formal squad designated marksman rifle for combat platoons and squad. Source: Military.com /27 April 2017/by Matthew Cox

7.62x51mm rifles tend to be reasonably light and maneuverable for a squad’s marksman while providing a good mix of accuracy and penetration out to about 600m with conventional ammo.

The M2010 sniper rifle chambered for .300 Winchester Magnum, provides good performance out to about 1,200m.

The typical .338 Lapua Magnum rifle only weighs about 2 pounds (1 kg) more than a comparable .300 rifle. A .338 rifle is capable of placing reliable hits well beyond a kilometer (0.6 miles). Compared to the M107 sniper rifle chambered for .50 caliber the .338 Lapua Magnum rifle has considerably less muzzle blast and flash and is much more pleasant to shoot with. The ammunition provides a more cost-effective option for long-range military sniping.

An Experienced Sniper

A couple of years ago, a Norwegian Telemark Battalion soldier with professional sniper experience explained in an interview what he had experienced during five tours in Afghanistan. There, he had countered fire assaults with precision fire, killed the enemy and completed the job efficiently and with accuracy. Annually, he shoots around 10,000 to 15,000 training rounds with various weapons; 3,000 to 4,000 rounds are used for sniper shots training. Three things are important for him: being in the wilderness, hunting and shooting.

He started his military sharpshooter career with the NM149 sniper rifle, a converted Mauser rifle. Since then he has used G3, PSG, MSG, and later the HK417 and Barrett .50 caliber (12.7mm).

His favorite is the PSG. He found it interesting that the military was looking at sniper rifles in the .338 caliber Lapua. In his opinion, that type of rifle comes a bit late, but when it comes it is good.

He would have liked to have that kind of a rifle in Afghanistan, he said. “There they missed a medium caliber, particularly in the years when skirmishes began,” he said. “Sometimes the distances were a bit long for the HK417, while the 12.7mm Barrett was brutal to use. They used it because they had to.” He would not enter the number of “kills” or talk about details of what he had been through. He experienced skirmishes and returned precise fire. He had been in situations where tracer and grenades from shoulder launched anti-tank grenade launchers closely passed by, but it was important to stay calm in such situations. It was not the first time he was in skirmishes where he had to return fire. “Training made the difference,” he said. “It is clear we had reacted differently if we were younger, or it was the first time we were out there in the danger zone. But with some years in the Afghan fields and together with other experienced soldiers, combined with much realistic training, one is more prepared.”