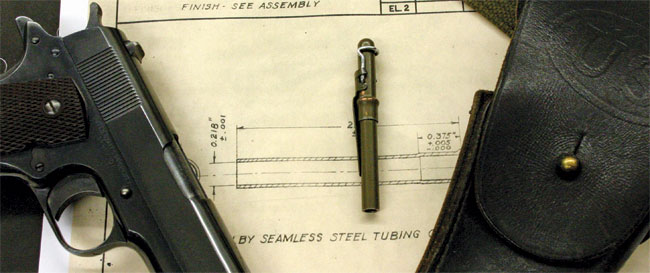

ABOVE: The Stinger in safe carry mode. Note how the saddle spring legs are locked in place by the pocket clip.

The speed at which the United States geared up for World War II in the days after Pearl Harbor must be the paramount industrial wonder of the 20th century. Peacetime manufacturing and occupations quickly became part of the war effort with an agility that seems impossible today. Many manufacturers with no experience in small arms were tasked with converting all or part of their operations over to produce them. Singer Manufacturing, Rock-Ola, and several divisions of General Motors are among these well-known to have made the hasty transition. A little known fact however, is that a firm famous only for producing writing instruments made an important contribution well beyond the humble pencil: The original Stinger pen gun.

The development and design of the Stinger is a fascinating story that combines the exigencies of war, an old-line American company, a shadowy “Army Captain” and a brilliant engineer to create what must be the safest, most compact pen gun ever made in .22 caliber.

Some details of this story are lost in time, but documentary evidence and research provides us with the following: in 1942, the Joseph Dixon Crucible Co. of Union City, NJ was contracted by the U.S. Government to develop a new, secret weapon for use by pilots and clandestine operatives. Joseph Dixon Crucible was the country’s leading manufacturer of mechanical pens and pencils, and developed the first mechanical pencil in the 1890s. It is still a familiar brand today with the Dixon-Ticonderoga line of pencils. The pen gun project was assigned to the company’s Director of Engineering, Charles R. Nichols, Jr.

Although the original government specifications are not known, judging from the resulting product, they clearly included the following requirements: minimum size/weight, safety from accidental discharge, and use of .22 short ammunition. Our research also indicates that it was specified that one end of the gun be rounded to provide for, shall we say, body cavity concealment. It is also likely that the fact that the resulting pen gun could fit into a cigarette package was no coincidence. As can be seen from the accompanying photos and illustrations, the resulting design fulfilled these requirements perfectly.

Most product development has fits and starts along the way, and the Stinger was no exception. The initial project was code named “Scorpion,” but this was soon changed to “Stinger” for reasons that aren’t clear now. By March of 1943, the design was finalized and manufacturing commenced.

The number of Stinger units produced is unknown, although they are very rare today. An example can be found on exhibit in the International Spy Museum in Washington D.C., while another is part of the ATF National Firearms Collection, (see Small Arms Review, Jan. 2008, page 90).

The specimen seen here is completely unmarked. No markings are visible on the other known pieces either, making it very unlikely to find this weapon on an ATF Form 3 or 4.

The Stinger is a one-time, single shot, striker fired, not-reloadable weapon. It is cocked and loaded during final assembly, when the body is crimped to the barrel, creating a shelf for the rim of the cartridge. Upon assembly, the striker is retained by the short legs of the saddle spring; with those legs acting as a sear. The body is made of drawn copper for malleability, with the balance of the parts made of steel. The barrel is of seamless tubing, and therefore not rifled.

The Stinger is extraordinarily safe to carry. This is important, since there is no provision for somehow making it safer or unloading it. The inherent safety of this gun sets it apart from other pen guns, which range from moderately unsafe to carry loaded to downright dangerous.

To determine if the Stinger is loaded, simply insert a rod down the barrel. A fired Stinger allows the rod to be inserted the full length of the barrel, while a loaded weapon will be noticeably shorter.

To fire the Stinger one must overcome spring pressure holding the trigger (pocket clip) in the “down” position and lift it to about 20 degrees. The trigger may then be slid fully to the rear along the saddle spring/sear while in the up position. Once to the rear, the gun is fired by pinching the trigger fully down with thumb pressure. The action of depressing the trigger, cams the two sear legs (which retain the striker) outward, freeing the striker to run forward under spring pressure to fire the cartridge. These three separate motions are easy to do quickly for one familiar with the Stinger, but could not occur accidently.

Although the .22 rim fire short is a rather puny cartridge, the Stinger loaded with this round would be adequate for its intended role: A tool to secure a real gun or a means to permanently prevent torture and the loss of valuable information known by the agent in possession of it.

While the designer of the Stinger, Charles R. Nichols, Jr. did not specialize in ordnance engineering, he did go on to work for Colt’s Manufacturing in the 1950s where he designed machinery to aid in rapid production of intricate parts. His contribution in developing a valuable tool for the war effort deserves recognition, albeit 70 years late.