ABOVE: George Salg fires the RAS47 during the semi-automatic testing at the Sportsman’s Club of Franklin County range.

Century Arms’ RAS47 & C39V2 Face the Music and Perform Mightily!

One would be hard-pressed to find more than a handful of companies in the last half century that have had the impact which Century Arms International and its variants have had on the US firearms community. Remember that almost all of the big names in firearms manufacturing started in someone’s garage, small gun shop or in the barn; Winchester, Browning, Remington, all started with a small shop. However, the world of Century Arms is different from those; it was born in the world of surplus weapons and international arms deals, not new manufacturing.

It started in the early 1960s with a discovery by William Sucher that the customers of his typewriter repair business were a much smaller pool to sell to than the customers interested in a surplus rifle he had taken in trade. Having a keen sense for business, Sucher and his brother-in-law Manny Weigensberg saw a market and began making contacts around the world for military surplus firearms and ammunition.

At the time in the US, there was a seemingly endless customer base for cheap military surplus rifles, handguns and ammunition. It’s not so different today; customers are eager for new surplus. Sucher’s new company, Century Arms, was ready to do what it took to fill that market with product—they traveled around the world, making deals and buying shiploads of surplus, bringing it to their facility in the old railroad building in St. Albans, Vermont, processing it and selling into their new network. There were a handful of competitors, but there was enough surplus to go around, and Century excelled at buying low and selling fast and high enough to build a powerhouse international arms business, all the while giving American and Canadian consumers a decent price on surplus. The company was formed in 1961 in St. Albans, Vermont, and there is a sister facility in Quebec (Century International Arms, Ltd).

In November 2000, Century moved to a new 100,000-square-foot warehouse/factory in an industrial park in Georgia, Vermont, where they are today. The headquarters was in Boca Raton, Florida, and moved to Delray Beach, Florida in 2004. As much of the military surplus around the world started drying up during the 1990s, more creativity was required to be a viable business, and Century began to manufacture US-made semi-automatic versions of many famous firearms. These included numerous rifle models including variants of the G3, HK33, FN FAL and a number AK clones in semi-automatic. These rifles, for the US civilian market, were legally manufactured with US receivers and foreign parts from surplus kits; then new regulations allowed for many new parts and receivers from the original factories. Many tens of thousands of rifles were made, and Century refined their engineering and manufacturing techniques.

Century also has had many deals with the US Government over the years, fulfilling non-standard firearms and ammunition requirements.

There were other considerations a military procurement person would need to take into account, which Century addresses professionally:

Fast availability of spare parts and service;

Convenient and direct access for inspection and communications;

Removal of cost and time for import/export permissions, international logistics and obtaining EUCs;

They are a prime manufacturer and can be quickly responsive to customer-specific requirements.

Century’s AKs coincided with a new “Made in the USA” requirement for military needs. The US military has many reasons for buying AK variants; much of it has to do with training, as well as supplying non-traditional forces with the AK, which may well be better suited for their use. When the US Government buys military items from another country, they have to comply with the non-transfer and End Use laws of the supplying country. That is just one more reason for the procurement to be from Made in the USA sources—there are no foreign obligations attached to these weapons, and they can be freely used for US interests. Even something as simple as using internal parts from a foreign country can call the non-transfer rules of that country into play, determining what the US Government can do with the firearm. That is too many strings for most procurements; almost impossible to track and comply with over the years.

It helps that Century has been so involved in US Government supply contracts in the past, and they were ready when SOCOM released an SBIR for “Foreign Like Weapon Production Capability.” That’s a “Small Business Innovation Research” program, regarding foreign weapons like the PKM, NSV and, of course, the AK.

But, which AK variants to offer? There are many designs to choose from, and Century has years of experience building these.

AK History and Types

With apologies to collectors everywhere for over-simplifying, there are two basic 7.62x39mm AK families—the AK-47 style made with a milled receiver, giving a more solid platform for the barrel and action; and the AKM style which is made with a stamped sheet metal receiver. If you require a true, in-depth understanding, we publish an 1100-page book called AK-47: The Grim Reaper which should satisfy any such need.

Century wisely decided to offer the C39V2 as a milled receiver AK-47 variant and the RAS47 with stamped receiver, so the customers can choose which features they desire most. We decided to run concurrent MIL-SPEC tests on both rifles.

Where did the AK come from? The stories have been told countless times, but there are two basic threads—ammunition for shorter, more realistic combat ranges and making a lighter weapon. During World War II, the Allies and the Axis weapon makers were noting that there was a need for an intermediate cartridge between the pistol rounds and the full bore rifle rounds—30-06 in the US forces, 8mm Mauser (7.92x57mm) in much of Europe, 7.62x54R in Russia. Ammunition was effective, but heavy and was a frequent overmatch for a rifleman regarding the ranges encountered. The US worked with .30 carbine (7.62x33mm) in the M1/M2 Carbine series, the Germans developed 7.92x33mm (7.92 Kurz) for their MP44 “Sturmgewehrs,” and the Russians had the 7.62x39mm M43, which didn’t get fielded until after the war, for the new SKS rifles.

General Kalashnikov, at the time a Sergeant rehabilitating from wounds fighting the Germans in 1941, was made familiar with the German Sturmgewehr and the shorter cartridge 8mm Kurz in 1943, and he took the concept of an “Assault rifle” and applied new information gained and upgraded this design for the Russian M43 cartridge. In conversations with General Kalashnikov over dinners in Serbia with this author, interesting revelations came about—that the MP43 wasn’t at all involved in internal operations, he said to look to the Garand. Length and some general shape ideas came somewhat from the Germans. After approximately six prototypes, the AK-47 was born in 1947, with a hybrid stamped receiver and its milled receiver introduced shortly thereafter to reduce production problems with the original sheet metal receivers. In 1959, after all of the sheet metal receiver issues were resolved, the AKM was introduced. Over 100 million AK variants have been fielded from many countries. Thus, Century choosing the two basic models of milled receiver and stamped receiver, in the style of the original Russian designs, was a good place to start.

Interchangeability

“Interchangeability” is the seven-syllable word that means so much in a military firearm—and unfortunately, much of the world’s AK inventory does not have it. During the Afghanistan military police armory program, with almost 400,000 weapons at 69 armories, this author was asked to supply a parts list for repair. No quantities were specified, and there were at least 15 AK variants in inventory, but no list of manufacturers/models. When I asked for that information, I was told, “You know, AK-47 parts.” After a brief internal meltdown familiar to most weapons people when dealing with non-firearms people, it was determined that the repair parts couldn’t be supplied without further description/info. Unfortunately, most of the AK variants in the US and US military inventories suffer from the same logistical problem. Actually, many of the AK variants from Romania and some other countries require hand fitting and marking for their own guns. This is totally unacceptable in a military-issued firearm. Century has nailed the 100% made in the USA–100% interchangeable within models bullseye. We tested several guns changing parts in and out, and all were perfectly functional. In my interviews with Century personnel, both in the field and in the factory, this was something they were very proud of. Another reason to consider Century’s full-auto AKs for field use, as well as the longevity of the company, and repair and replacement parts availability is guaranteed.

At the Factory

Rick Schomer, the COO of Century, came from the Detroit automotive manufacturing base and is half way to getting Century an ISO9000 rating in First Quarter 2018. This will be an added feather in the cap of Century’s manufacturing credentials, and we had a nice “Vision” discussion regarding future programs for Century. We were also able to meet with Operations Manager Jeremy Bates and Manufacturing Supervisor Jim Putnam on our tour through the facility. This author’s last tour through Century’s Vermont locations was during the First Gulf War at the old railroad building and … what a change. Century’s facility was modern and extremely well organized to the flow of production. The investments made in infrastructure and physical plant are amazing and are paying dividends in quality control and smoothness of production. The resulting products that we tested are a testament to the organization and workers at the factory.

How the Test Was Designed—Cooling, etc.

When Century contacted SADJ to organize a MIL-SPEC test, the two-receiver model situation had to be taken into account. We were aware that these rifles had performed remarkably well in Century’s internal testing, but as almost all manufacturers will attest, there is that, “So, your factory did the test, and these were the fantastic results, huh,” which may come from many potential customers. The idea of the testing was to have SADJ design and perform one of our MIL-SPEC tests for them. We needed to not only show the endurance under heavy firing for the end users’ perspective, but provide quantifiable data that a procurement person could use. The logistics people who must prepare an inventory want to know all of the details. Our proposed test was for two rifles, one of each model, each firing 12,000 rounds. We wanted the following answers for Century’s customers:

Are these Century rifles up to a MIL-SPEC?

Will they perform through a US-style MIL-SPEC test?

Are the parts interchangeable for full-function testing?

What are the Mean Rounds Between Failures?

What is the barrel life, and how is the dispersion degradation?

Can we ascertain that both the logistics groups and the end users will be satisfied with the weapon system?

SADJ could ascertain the MIL-SPEC issues very easily with a properly designed test. Barrel life and dispersion are more related to how that test is performed, leading to the most crucial questions we had to design the test for, which are elaborated in number 6 above. Most end users intuitively consider the famous four qualities in firearms that the likes of Eugene Stoner, L. James Sullivan, C. Reed Knight, Jr. and many others have polished over the years: Is the weapon design Simple, Reliable, Robust and Accurate? If it doesn’t meet those requirements, it’s hard to get it accepted by the professionals who have to use it. Most end users will look at how reliable it is and ask whether it can withstand heavy use—long bursts while they provide cover, “mad minutes” in tough firefights? All questions that when answered, provide confidence and comfort for the warrior who has the weapon as a life-saving or life-taking tool.

Logistics personnel have different requirements in mind—it’s not all combat, it’s mostly about training sessions, longevity, chain of supply and cost accounting. Can we get replacement parts? In this case, there is the added burden of knowing unskilled persons may be using these. The planned purchase of a new weapon system requires many factors be taken into account—and SADJ had to design a test that could answer these questions as well. The tests were designed to answer these questions in a proficient and comprehensive manner. We invite our readers to understand that while this type of test sounds like fun, it is in fact a grueling and demanding task—many hours and many people working to keep the details in order to not invalidate the terms of the test. Fortunately, the Century range crew was experienced in firing a lot of rounds and enjoy it while they are at it. There’s an old saying; “Any day at the range is better than a day at the office.”

It was decided that the best way to proceed was for the factory to provide the firearms, the ammunition, the shooters and technicians and the range, and this author would be in a supervisory capacity to ensure protocols and temperatures were adhered to and perhaps do some of the test firing. In order to speed up the testing time, and allow a natural test of barrel erosion and dispersion, Century designed a four rifle cooling tent. It’s important to “Rest” the barrels and return them to an agreed ambient temperature between each firing. For those who want to engage in this type of test, dropping weapons in water or using other methods that cool too rapidly are not effective in getting true results. That is a different type of element torture testing.

The need we had was to simulate years of training interspersed with long periods of no use, and not to wow a crowd with clouds of steam. Ambient temperature air sent through the barrels at perhaps 100psi will speed up the removal of heat and shorten the testing time without compromising the barrels. Century’s design of putting the air over the complete firearm worked very, very well. If you do this type of testing a lot, then remember that compressors mean moisture and add some condensing to the system. We utilized two shooters at a time. Some of the details of what we arranged for the initial test firing protocol changed as we discussed the on-going tests with Century and their engineers. Essentially, they were confident that the temperature on the barrels could go higher than our first recommendation of taking the temperature down to around 80° F before returning to firing.

To the Range—3 Days of Testing

On a beautiful June morning, we mustered at the Sportsman’s Club of Franklin County on Maquam Shore Road in St. Albans Bay, Vermont (www.scfcvt.org). We set up the loading stations, the firing line, received our Safety Briefing from Range Officer Maynard Pearo and performed our first testing regimen. Century Engineer Sam Gagnon and Century Director of Global Procurement Kevin Quirino were there to supervise the testing and fill in information for SADJ as we went.

Rate of Fire testing: Both the RAS47 and C39V2 had rates of fire from the factory between 550 and 600 RPM, until they were quickly broken in—this is normal as finishes wear enough to not impede action movement, and both rifles settled in at 700-720 RPM very quickly.

Century had chosen to use 100% made in the USA magazines, of course, so Magpul’s PMAG 30 AKMDE 30-round AK magazines were used—several hundred of them were lined up and filled (www.magpul.com). Through the course of the test, there were no problems at all with the magazines, and the magazines withstood the “Polish style” mag change—with full magazine in left hand, operator slaps through the flapper mag release and rocks the empty magazine forward, inserts the new full magazine, rotates the rifle to the left and charges over the rifle with the left hand.

The test itself was pretty basic—fire enough rounds to simulate a range visit by a soldier, then cool it down as if it were in the armory, then repeat the cycle. At certain intervals, cleaning and inspection were called for, and at other intervals, there were factory-mandated small parts and spring replacements. Accuracy was checked at intervals. This gives a special picture of performance over long periods to the logistics specialist.

The cycle of fire for both models was the same and was done concurrently:

Three 30-round magazines, total of 90 rounds, fired semi-automatic with approximately 1-2 seconds between rounds.

Two 30-round magazines, total of 60 rounds, fired full-automatic in 5-round bursts with approximately 3 seconds between bursts.

This was 150 rounds fired, a fairly typical range qualification.

Mike Wells and then Nate Stevens were on loading detail; George Salg and Will Barbeau, Century Mechanical Engineers, were the firers.

We started with rifles at an ambient temperature of around 90° F, and at the end of the firing cycles, the temperature was generally around 600° at the muzzle and 650° at the gas block. At this point, the rifles would go to the cooling rack. The cycle was then repeated.

At 1000 rounds, a standard cleaning was performed, with quick inspection.

At 2000 rounds, a standard cleaning was performed, with quick inspection.

At 3000 rounds, a standard cleaning was performed, with more in-depth inspection.

There were 4 cycles of the above per firearm until 12,000 rounds were reached.

Century had mandatory parts changes, but they were mostly for the springs. Their first-generation springs were a little weaker than engineering liked, and the second generation had been upgraded and ordered—we had not received these yet. So, the protocol was to change recoil and extractor springs at 4000-round intervals.

C39V2

3450 rounds—broken extractor spring changed, stoppage

4800 rounds—during inspection, broken recoil spring changed, no stoppage

6750 rounds—changed broken extractor spring, stoppage

7050 rounds—changed recoil spring, no stoppage

8000 rounds—special gas port cleaning during maintenance, running a bit sluggish

10,500 rounds—changed broken extractor spring, no stoppage

12,000 rounds—changed broken extractor spring, on final inspection

The C39V2 experienced two stoppages that were not related to dud primers and two failures that required parts changing, which were the same events. This is an MRBS—Mean Rounds Between Stoppages of 4000 rounds and an MRBF—Mean Rounds Between Failures of 4000 rounds. Considering the accepted numbers for the US M16A2 are in the 3600 round area, this is an excellent performance.

RAS47

3390 rounds—broken extractor spring, stoppage

4800 rounds—broken recoil spring, stoppage

6690 rounds—broken extractor spring, no stoppage

7290 rounds—spinback, stoppage

9000 rounds—changed broken hammer spring, no stoppage

9540 rounds—spinback, stoppage

9840 rounds—broken firing pin, stoppage

10,050 rounds—changed extractor spring, no stoppage

12,000 rounds—changed recoil and extractor springs, no stoppage

The RAS47 experienced five stoppages that were not related to dud primers and three failures that required parts changing. This is an MRBS—Mean Rounds Between Stoppages of 2400 rounds and an MRBF—Mean Rounds Between Failures of 4000 rounds. Considering the accepted numbers for the US M16A2 are in the 3600 round area, this is also an excellent performance.

I would like to note at this point that the required factory changes on the Gen 1 springs at 4000 rounds were pretty close to when these needed to be changed out, and the Gen 2 springs have much longer life cycles, addressing that issue.

7.62x39mm Ammo Choice

Both the RAS47 and C39V2 series are basic 7.62x39mm weapons. As such, they’re expected to function with any such round made to feed in the system. This can provide a withering variety of manufacturers and surplus, as well as some variants in projectile and powder. What would be the standard military load would be the (M43) 57-N-231, which has a steel core projectile and can no longer be imported to the US. Instead, we chose a generic 7.62x39mm round with 122gr Full Metal Jacket projectiles. Unfortunately, the rounds had a number of duds with fully struck primers and some inverted primers. These were deducted from stoppages; they’re ammo issues, not a problem with the rifles.

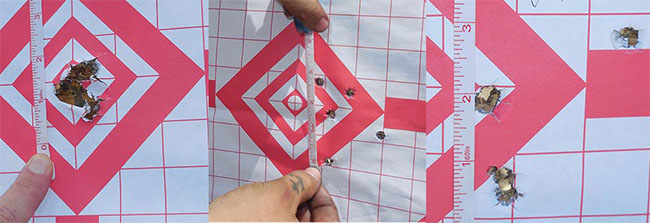

Accuracy Testing – All Firing Done Off Hand with Scope

The C39V2 was expected to be more accurate, due to the bedding of the barrel in a milled receiver. In the first photo, the first group shows a group of less than 1.5 inches, at 50 meters. The second photo shows the 6000-round group opening up a bit to around 3 inches, and the final 12,000-round group is tightened to under 2 inches. This is not a significant degradation in accuracy.

The RAS47 with its stamped receiver was expected to have a lower degree of accuracy, still very acceptable to AK variants in comparison. The first group is around 2.5 inches at 50 meters. The second group is at 6000 rounds and shows approximately 3 inches. The 12,000-round group has spread to around 5 inches.

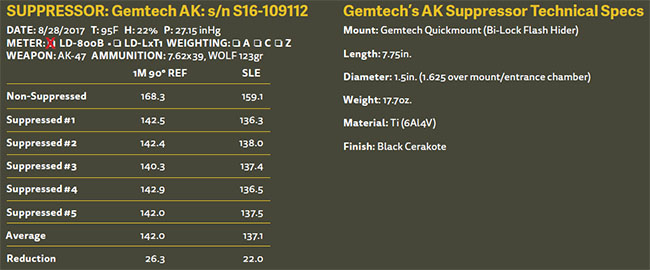

Sound Suppressor?

Century went through their options for a company to do design work for a suppressor to issue with the RAS47 and C39V2 and chose Gemtech. This author did not have a chance to personally test the suppressor but obtained the following test chart from Dr. Philip H. Dater of Antares Technologies, one of the founders of Gemtech. AK variants are notoriously hard to suppress, due to the piston operation—Gas is vented after the piston leaves the port block and vents into the atmosphere. This is not conducive to suppression; the expanding hot gases here are not easily contained. Any suppressor, therefore, is dependent on what can be taken from the muzzle and will suffer a bit on suppression. Dr. Dater was using Wolf 7.62×39 in this test, and the Gemtech AK suppressor is the production version and is all titanium with Bi-Lock mounting. The original Russian suppressor, the PBS-1, utilizes a rubber wipe on the muzzle end, and the wipes are generally issued with the subsonic ammunition. The suppression tests were taken at the standard 1 meter 90° to the side of the muzzle, and then SLE—Shooter’s Left Ear. Obtaining a dB level below 140 is one aim of suppressor design; under that number OSHA considers hearing safe for the shooter. This is very important in training, as well as in the field.