Science Fiction Becomes Science Fact as Navies Explore Novel Ways to Defend Against Enemy Divers

Between imagination and reality, a shadow flickers in the gloom. Your eyes and brain strain for another glimpse. Great white? Enemy diver? Killer whale? In a flash, the living torpedo races in, and a man-made mechanism attached to its head promises agony and death.

In the split-second left, you swing the gun against the water and fire. The monster explodes into a chaotic mist of blood and ragged chunks of flesh. Almost instantly, sharks fight each other to clean the water. And, the monster? The smiling, chirping porpoise of television and movies has morphed into a porpoise with a perverse purpose.

Anyone who follows weapons development knows this is not science fiction. While we thrilled to “Flipper,” 1960s navies, ours and theirs, trained intelligent sea life to serve often deadly purposes, one of the first being attacking hostile divers.

To counter these malicious mammals, or enemy frogmen, friendly divers had few options—single-shot spear guns were really suitable only for hunting fish, although a lucky hit might kill or incapacitate an unprotected diver. Most propelled their spears with large, elastic bands. While freakish guns might attain 30 feet of range, most guns barely managed a dozen feet.

In the 1970s, divers got the Shark Dart. This was a long-handled needle that emptied a cartridge of compressed carbon dioxide into the target. The concept promised a fantastic leap forward; the internal explosion of CO2 would instantly halt the attack and send the sushi flying for the surface. Even better, the CO2 would freeze the point of entry so there would be no cloud of blood and guts to attract predators. In reality, the blast, while incapacitating the fish, usually caused an explosive vomiting of the target’s innards.

The “bang stick” is still well-known to military and civilian divers. The business end of the device is pressed to the target to fire a firearm cartridge. The hard contact is vital as projectiles alone simply pass through the fish: Much like the shark dart, it is the bang stick’s shock wave and the explosion of expanding gases that do the damage.

Packing a regular gun underwater introduces more problems than rust. Water will stop most handgun bullets in under 10 feet and most rifle bullets in under 20. Water in the bore is a blockage, and many guns will explode if fired with the barrel full of water. Even when the gun is raised into the air, if sufficient water remains in the barrel, the same thing can happen. Capping the muzzle and hoping a chambered cartridge will prevent water entering is only good for the first shot, if it works at all. Ammunition may fail because water has entered it under pressure. Semi- and fully automatic guns have rapidly moving parts, and when water is trapped, say behind a bolt, it can stop the action completely.

The underwater discharge is also hard to conceal. The noise is excruciating for the shooter and anyone nearby. The event creates a lot of gas, and this emerges dramatically as bubbles. And, even underwater, there is flash.

Solutions can be engineered. Semi- and fully automatic guns can be re-designed to allow water to be expelled. Ammunition can be waterproofed. Suppressors muffle sound, diffuse bubbles and hide the flash. Covers break up the gas bubbles escaping the cylinders of gas-operated guns. Bursting barrels are avoided by cutting grooves into the bore so propellant gases can push ahead of the projectile and eject water out of the bore ahead.

But, the bullets themselves are the real problem. In good conditions, a diver might be able to see a target at 100 feet or more. The energy required to push the water aside and the drag of the turbulence limit the bullet’s range. So, researchers developed projectiles with better underwater ballistics. Most designers arrived at long, nose-heavy, dart-like projectiles launched from smooth bore barrels. These are variously called darts, “nails” and “flechettes,” (French for darts.) Some are stabilized by fins angled to induce rotation. The long lengths of the cartridges and darts dictated some unconventional-looking firearms.

A major improvement was applying the self-sealing cartridge. The idea dates back to at least 1900 when an American, Joseph E. Bissell, patented his invention. His special cartridge propels a bullet by a piston in the casing. The piston is caught in the cartridge neck, or a muzzle trap, and the projectile continues on its way. The flash, bang and smoke are trapped behind the piston, solving several problems.

The image of desperate hand-to-hand combat in the deep grips the imagination, but development of underwater guns has been spurred just as much by threats from trained mammals like porpoises and sea lions. These animals can be equipped with cameras, weapons, retrieval and capture devices and explosive charges to be delivered, planted, or attached to, ships and submarines or detonated in suicide missions.

The ambitious USN program originally incorporated porpoises, pilot and beluga whales, seals, sea lions and even cormorant diving birds.

The conscripted animals have their own designations according to their specialty. The MK 4 MMS (Marine Mammal System) porpoise finds and marks tethered and floating mines.

The MK 5 MMS is a Sea Lion trained to find various equipment, often training mines. It can easily locate a submarine for rescue or less pleasant purposes.

The MK 6 MMS is a Sea Lion trained to attach a clamp to a diver’s leg. Porpoises and sea lions are adept at locating lost and injured divers. During the Vietnam War, trained porpoises goosed North Vietnamese divers with a barbed hook attached to a balloon to pull them to the surface. This ignominious end was enough to make the NVA give up their attempts.

The MK 7 MMS porpoise seeks mines on the sea bottom. Porpoises’ natural metal detectors can distinguish between metals and even find their targets buried in mud and sand.

The MK 8 MMS porpoise picks safe routes for landing craft heading for the beach.

When fitted with various handles and harnesses, most MMS can carry cameras, lights and sonar transmitters to “paint” undersea objects.

Trained porpoises can patrol 24/7. Unlike us, they don’t breath automatically, so they have to stay awake to stay alive. But, because they also have to sleep, they put half their brain to sleep; they are ideal government servants.

The U.S. Navy won’t entrust sea mammals to make life-or-death decisions about divers, but at least two Soviet Spetsnaz divers reportedly died in Vietnam when a trained porpoise wrecked their breathing equipment. In the late 1970s, divers of the same Spetsnaz “Delfin” (Russian for Dolphin) program killed several porpoises in Nicaraguan harbors.

In a lighter vein, The Guardian, a stalwart of the British tabloid press, published a report in 2005. A “respected accident investigator” warned the world that U.S. Navy Killer Porpoises armed with toxin-tipped darts had escaped their pens during Hurricane Katrina and might well be stalking wind surfers and divers. No attacks are recorded.

More recently, porpoises have been deployed in the Middle East. The U.S. still uses them to patrol harbors and detect mines. The Palestinian government, Hamas, reported capturing a porpoise off Gaza in 2015 armed with a gun, poison darts and a camera. It was later reported the porpoise was in fact a robot.

When the USSR collapsed, Russia dropped their military porpoise program for lack of money. Some animals were sold to Iran while others entertain tourists in the Crimea. Iran still runs a military program.

With economic recovery, Russia revived the porpoise program. This is no reason for porpoises to celebrate. In earlier Russian training, 2000 porpoises allegedly died learning to carry kamikaze charges to ships. (Hopefully a similar program will be introduced for suicide bombers.) Porpoises also carried CO2 lances similar to Shark Darts and were even parachuted into action.

Marine mammals face increasing counter-measures. Electronics can identify “working” creatures and heat-seeking anti-mammal detectors are possible. Armed underwater “drones” and robotic patrolling torpedoes are threats. Electronic measures to “jam” the porpoise’s echo-location abilities and electro-magnetic navigation are likely. Occasional mass beachings have been blamed on experiments with these.

Underwater warriors date back to several hundred years B.C. Various cumbersome systems have existed for centuries, but the first breathing apparatus to enable independent underwater swimmers was developed and exploited by Italian divers just before World War II.

When it came to arming the divers, Russia took the lead in the 1960s. A major spur was likely the “Buster” Crabb case.

In 1956, the Russian cruiser Sverdlov arrived at Britain’s Portsmouth harbor carrying Nikita Khrushchev on a goodwill visit. It didn’t go well after someone brought up politics during dinner. Two days after the ship departed, the British announced their famed and beloved military diver Lt. Commander Lionel “Buster” Crabb had vanished, coincidently near Portsmouth, while testing new diving equipment. Oddly, swimming proficiency wasn’t required to be a Royal Navy diver, and as Crabb was a terrible swimmer, an accident seemed plausible. Far more likely, Crabb was examining the Russian ship. A year before, on a similar mission in Portsmouth, he had discovered a clever retracting propeller on another Russian warship.

The “accident” story began to unravel a few days later when the angry Soviets said they had spotted a diver near the ship. The press and politicians went wild. Theories included Crabb being dragged through an underwater door in the hull and spirited to Russia to be brain-washed and forced to train Spetsnaz divers. Just over a year later, a body in a navy diving suit was recovered nearby and identified as Crabb’s, despite the absence of head, hands and DNA testing.

The most credible explanation emerged when a former head of Soviet intelligence, by then retired in Israel, reported a Soviet officer on the Sverdlov had seen a diver surface, borrowed a sentry’s rifle and shot the diver in the head. British records of the incident are sealed until 2057.

Whatever the story, the Soviets were soon in search of effective underwater weapons for their 3,000 frogmen. Ivan Kasyanov’s new technology, the supercavitating projectile, put them in the lead.

If you’ve watched an outboard motor, you’ve seen cavitation. Those tiny bubbles materializing from nowhere are actually water vapor. Normally, water boils and becomes vapor (steam to us luddites) at 212 degrees Fahrenheit or 100 degrees Celsius. However, if you ever boiled water at a high altitude, you likely noticed it boiled at a lower temperature. This occurs because the pressure of the atmosphere is lower as you get higher. It is pressure that keeps water from vaporizing—the lower the pressure of air or water, the easier it is for water to vaporize.

A ship’s propeller pulls water from ahead and pushes it out behind. As water passes the propeller blades’ leading edges, the sharp lowering of pressure allows the water to vaporize and form small bubbles. These are swept out behind and quickly collapse with a small pop. The process of forming bubbles is called “cavitation.” The hissing pop is what sub-hunters listen for. As well as noise, cavitation can cause erosion of the propeller, and much effort has been expended to eliminate it. Since higher speeds result in greater cavitation, one answer for submarine designers has been to increase the number of blades. These can then turn more slowly to produce the same thrust without causing cavitation.

But, cavitation can be very helpful when you want to move something through water at high speed. Instead of using a needle-like, stream-lined dart, Kastanov gave his “flying nail” a purposely blunt tip. When propelled at high-speed, his tip caused a bubble of vapor to form. This stretched back along the sides and encased the entire projectile. Suddenly the nail was flying through thin vapor, not thick water and at a previously unachievable speed. Creating this by design is called supercavitation.

Dmitry Shiryaev of Tula first proposed the four-barreled underwater B-VI-307 gun. It fired Kasyanov’s supercavitating dart with a rocket assist. Combined with Bissel’s self-sealing cartridge, this remarkable device was too complex for easy manufacture, but led directly to the SPP-1, a very similar four-barrel gun.

Designed by Vladimir Simonov (not the SKS Simonov) the SPP-1 is still produced at Tula as the updated SPP-1M and sold internationally. Each barrel holds a cartridge firing a supercavitating dart from a self-sealing cartridge. The trigger is double-action. Each pull cocks and releases a striker to fire a new round from one of the smooth-bore barrels. Shots are deadly out to 60 or more feet in shallow water and roughly the same in the air. The operator breaks open the weapon to load a cluster of four rounds. The gun was adopted by the Soviets in 1971 and soon copied by the Chinese as the Type QSS05.

The U.S. was also busy. Early experiments followed the Soviet flirtation with rocket-propelled weapons and with the same mixed results. MB Associates, makers of the unique Gyrojet, displayed an underwater model of their pistol in the 1960s.

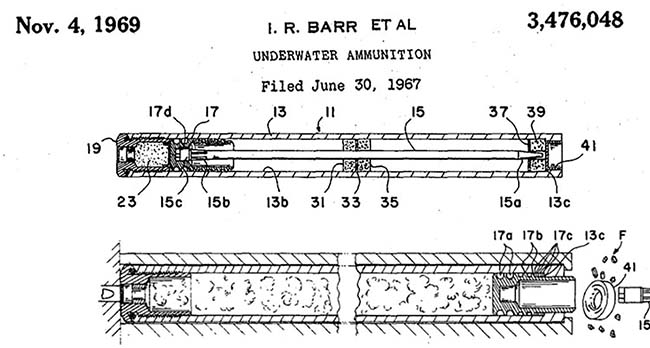

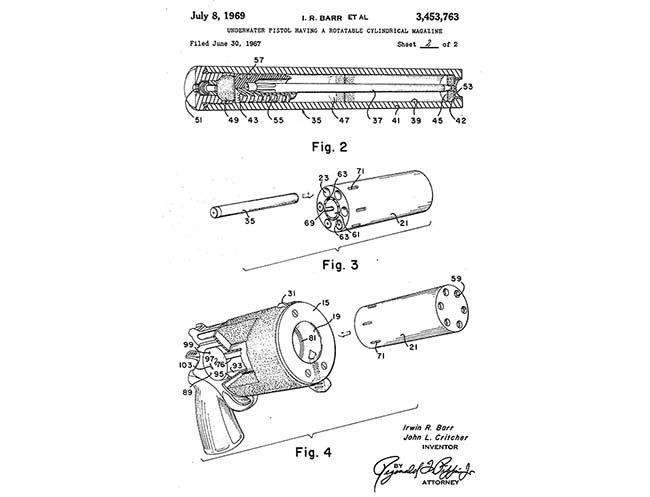

AAI Corp. (founded as Aircraft Armaments, Inc.) patented a design in 1969 by Irwin. R. Barr, a founder and CEO of AAI. The design surrounded the six rotating barrels with a thick floatation jacket. Again, a self-sealing cartridge was used to propel a dart.

The American Mk1 Mod 0 Underwater Defense Gun (UDG) followed in the early 1970s. The Mk1 Mod 0 is a six-barreled pepperbox. The six-barrel cylinder is inserted through a hinged door on the left of the gun and rotates inside with each double-action pull of the guardless trigger. Each of the six barrels is loaded individually with a stainless steel Mk. 59 Mod 0 cartridge. When a firing pin strikes the primer, the propelling charge launches a 4.25-inch dart. The propellant gases remain trapped in the self-sealing, barrel-length casing, and there is little signature of bubbles, flash or noise. From the mid-70s to the mid-80s, it was available to American divers and special operators. It was so well-cloaked, the U.S. Navy sent a photographer to photograph its rare UDG example specially for this article.

When the German Heckler& Koch (HK) P11 became available after 1976, 100 were acquired by the USN to replace the Mk1 Mod O. The HK P11 is a five-shot dart firing weapon. Unlike the American Mk1 Mod 0, the barrels do not rotate. Each self-sealing cartridge is fired in turn by electrical impulse. The individual barrels are not user-reloadable like the American gun, but the barrel cluster is easily replaced with a fresh one. The used assembly can be returned to HK for reloading in training but is expendable in combat.

The success of the Soviet SPP-1M led to the development and adoption of the Soviet APS underwater rifle. This was another Simonov design. It is gas-operated with an AK-style rotary bolt. It was adopted in 1975 and looks like an assault rifle with a massive magazine. The unique magazine shape is the result of the magazine spring and follower at the rear. Like the SPP-1M, it was made at Tula and sold internationally. It fires from an open bolt and has a smoothbore barrel. The receiver is cut away to allow water to get out of the way of the bolt. The mag holds 26 120mm-long, 5.6mm rounds with steel darts. A gas regulator lets the gun be adjusted for depth. In depths of less than 20 feet, it can reach out an impressive 100 feet. Go below 100 feet in depth and the effective range drops off to under 40 feet. Communist China produced a copy of the Soviet gun called the QBS-06. The Chinese version holds 25 rounds in a magazine that dispenses with the distinctive second square of the APS mag.

For divers guarding ships and installations underwater, the APS was fine, but the gun’s performance and short life when fired in the open air precluded it as a dual-purpose assault weapon. A diver boarding a boat or heading for land combat had to carry both a dedicated underwater gun and a terrestrial assault rifle sealed in a plastic bag.

In the 1990s, Russia offered up a combination underwater and open air weapon. This is termed the “dual-medium” ASM-DT, the “medium” being water and air. The ASM-DT has two magazines set side-by-side and fires either underwater darts or normal 5.45mm AK-74 ammunition through the same barrel. The operator chooses which he wants to fire. The rifling is shallow so as to approximate a smooth bore for the darts but deep enough to provide spin for the 5.45mm. The ASM-DT bore has additional grooves to allow gas to flow ahead of the bullet and blow water from the barrel.

The long darts are housed in the same magazine used by the APS, and the everyday 5.45mm rounds use a standard AK-74 magazine. The weapon has a folding stock and can be dressed with accessories from grenade launchers to scopes to silencers. Known as the “Sea Lion,” the ASM-DT entered service in 2000. It appears various “shorty” models have been tried. And yes, there is a self-sealing grenade cartridge.

The next breakthrough in a dual-medium assault weapon appeared in 2013. The new Russian ADS uses a supercavitating bullet and eliminates the need for the long darts and dual magazines of the ASM-DT. The new bullpup fires a special 5.45mm round that reaches out to 75 feet underwater. The gun can fire the new bullet or regular 5.45mm interchangeably from its 30-round magazine. International sales are being courted.

A major plus of supercavitating ammunition is its ability to enter or exit water without deflection. The projectiles can be fired from underwater at targets above, or, because it works both ways, shipboard weapons can fire at incoming torpedoes. The velocities attainable also mean a diver or robot can fire a lethal underwater shot into the most massive submarine.

The Norwegian firm of DSG Technology has sold its CAV-X Multi-Environment Ammunition (MEA) to several clients, the U.S. among them. The projectiles can be fired from standard weapons. They are stabilized by spin imparted from the weapon’s rifling and are as effective as regular ammunition on land. The .50 bullet can travel up to 200 feet underwater, the 7.62 NATO about 70 feet and 5.56 close to 50 feet. Smaller calibers are offered as are larger examples up to 127mm. It is being made in the U.S. and is in current American inventory.

In the 1990s, the Soviet VA-111 “Shkval” supercavitating torpedo awed the west. A nozzle in the nose shoots out a small portion of exhaust to be swept back along the body. The torpedo moves through bubbles at reported speeds of 230mph.

This active cavitation method isn’t limited to torpedoes. At least one U.S. patent was granted in 2005 for an underwater projectile that relies on self-contained jet propulsion for forward motion while a vent in the nose allows some of the exhaust to exit to the front and form bubbles much like the Soviet torpedo. This system can enable friction-reduced passage and longer ranges at lower speeds where cavitation wouldn’t otherwise occur.

The future of underwater firearms will no doubt hold more technical advances, but the range of current weapons already exceeds a diver’s vision underwater. As target detection and identification evolves, newer types of weapons may be attached to trained creatures, drones, buoys or vessels’ hulls and divers. As long as someone has to go in the water, underwater firearms will be with us.

All photos are used with permission. My thanks to Lt. Benjamin T. Anderson, Joseph “Jay” Bauser, Mel Carpenter, Guy N. Dentay, Vitaly Kuzmin, Max Popenker, James Samalea, Lt. Mary L. Sanford, Dan Shea, Paul Taylor, Joseph Trevithick, Movie Armaments Group and the late R. Blake Stevens.

Terry Edwards has done numerous articles for Soldier of Fortune, Small Arms Review and Small Arms Defense Journal. His books are available on Kindle.