ABOVE: 100,000 bears only this stamp and not the usual stack of serial numbers.

A ceremony was scheduled for August 21, 1943, at the John Inglis Company. The first of the morning shift arrived in darkness, announced by the steel-on-steel screech of streetcar brakes. When the accordion doors opened onto Toronto’s Canadian National Exhibition grounds, a group of workers stepped down. Inglis was running two 10-hour shifts a day, reserving the remaining four hours for maintenance and cleaning. Most of the almost 18,000 workers entered from King Street to the north of the plant, but these were early for a reason.

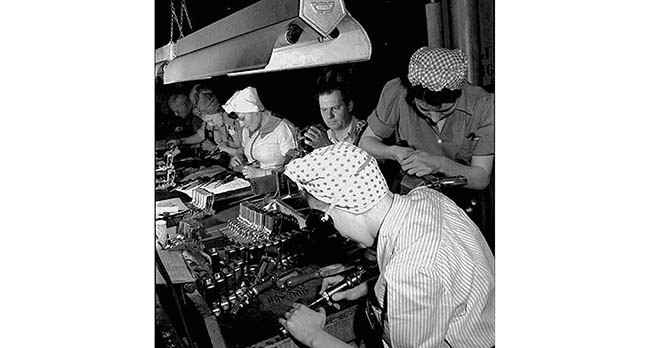

Cradling infants, holding children’s hands, and draping sleeping toddlers across their shoulders, the parents entered the Coliseum and gave over the national treasure to the young women of the crèche. The “girls” were all volunteers, including the daughter of the John Inglis Company’s owner and several of her former schoolmates (my mother among them). The men and women, an even split on the production line, then hiked across the railyard to three dozen red brick buildings and the 5,000 machines that were Inglis.

The ceremony began before lunchtime. They were celebrating the building of 100,000 Bren guns at Inglis. The band of Number Two Depot played. Speeches were made. Miss John Inglis gave a corsage to the new Mrs. Bradley to celebrate her recent marriage. Finally, Bren gun number 100,000, complete with a small silver plaque on its butt, was presented to Dr. Liu Shih Shun, the Chinese Minister to Canada. Maj. Gen. Pia Kiang then posed with Miss John Inglis and the gun. Watching proudly were Maj. James Emanuel Hahn, DSO, OBE and MC, the owner of John Inglis Company, and Harry John Carmichael, Joint Director General of Munitions Procurement and Canada’s top munitions engineer.

Gen. Kiang had been there before. He had established the purchasing team from China in Washington, D.C., and came to tour Inglis in June of 1941. The Nationalist Chinese were fighting the Japanese and needed 8mm Bren guns. Inglis was ready to oblige. While he was there, Gen. Kiang had his High Power and passed it to Hahn. He asked if Inglis could make them. Hahn was no slouch as an engineer, but he deferred to the tall man beside him. There was no one better qualified to answer the question than Harry J. Carmichael.

Carmichael, the second of four brothers, was born in 1891 in New Haven, Conn. His Scottish-born father, William, was an engineer and his mother, Mary, was from Ireland.

By his mid-teens, Harry was making exceptionally good money in the New Haven offices of hardware maker, Sargent and Company. But money wasn’t everything. He left the swivel chair and took a substantial pay cut to work as a machinist on the plant floor. There he educated himself in engineering and by age 21 knew his profession thoroughly. He was also a really good baseball player. Across the border in Canada, the McKinnon Co. of St. Catherine’s, Ontario, noticed him and recruited him to work as a pattern maker … and to captain the company baseball team. At the time, the Canadian-American border was trivial, and, as his parents were both born British subjects, Carmichael’s Canadian citizenship was automatic. Five years after arriving in the McKinnon factory, he was assistant manager.

General Motors Canada bought McKinnon in 1929 and took on now-president and general manager Carmichael. In 1936, GMC lured him to Oshawa as a vice-president and general manager of General Motors Canada.

WWII began for Canada three years later, in 1939, and General Motors was soon devoted to munitions production. In 1941, GMC loaned Carmichael to the Government of Canada as assistant chairman of the Wartime Requirements Board. A month later, he was promoted to director of the munitions production branch and director general of gun and tank production.

He’d barely found his office when, he became joint director general of munitions procurement. There was no higher unelected office. He answered only to the cabinet Minister, C.D. Howe. Carmichael could walk into any munitions factory in the nation, order any changes and hire and fire at will. He made a dollar a year.

He reputedly “annoyed a lot of people that stood in his way” … until production soared. He arrived at GM with a hard-nosed anti-union and anti-labor reputation. The war reversed his attitude. He was soon giving the munitions workers praise for their war effort. He went on the national Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s radio network to say so… and chided Canada’s industrial owners and management to match them.

“Yes,” he nodded to Kiang and Hahn, Inglis could make the guns. Carmichael’s ground-up education enabled him to visualize every operation required to create any machine. But there was the sticky matter of drawings. There were none: The originals were trapped in occupied Belgium. Gen. Kiang offered to leave his personal gun and promised to round up several others for “reverse engineering.” The summer of 1941 was a desperate time.

Two years later, in August 1943, the Inglis workers at the Bren gun ceremony had earned the short celebration. Lunch was served. Hands were shaken, backs were slapped, and Harry Carmichael reiterated his praise of the workers. By now, the John Inglis Company was making Bren guns, .303 Browning machine guns, Boys .55 caliber anti-tank rifles, Polsten anti-aircraft guns, and was now tooled up and poised to make the 180,000 Browning High Powers requested by the Chinese.

The history of the High Power has already been admirably covered in SAR. The Fabrique Nationale Grande Puissance, the High Power, is a basic Browning design, refined and updated by Dieudonne Saive of FN. It fires the 9mm Parabellum cartridge and remains in production and use. Ironically, the high-capacity magazine that vaulted the High Power above its competition was not something Browning cared for and was added by Saive.

The early FN-made High Powers were sold to several countries, China among them. The Chinese had been fighting the invading Japanese since 1937. They bought 5,000 FN-made High Powers, and would have bought more if Belgium weren’t overrun by Japan’s ally, Germany.

The John Inglis Company offered China a solution. Inglis was an old name, started by John Inglis and partners in 1859 to make farm equipment in rural Guelph, Ontario, Canada. John Inglis died in 1898 and the following year his sons moved the factory to Toronto to make engines for ships and factory power plants. The company survived the death of John Inglis’ sons, but it didn’t survive the depression.

Enter Maj. Hahn. In the mid-1930s, Hahn was an able and well-connected middle-aged businessman and like Carmichael, American-born.

He was born in New York City in 1892, the son of Alfred and Eugenie Hahn, who had arrived from Germany just two years before. In 1898, they moved to Ontario, Canada. Hahn joined the Canadian militia and was a Captain by twenty-two. Within days of WWI beginning in 1914, he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. To add a veneer of maturity, he added four years to his age when he joined, claiming to be born in 1888. He ended the war a Major, decorated with the Military Cross and the scars of three wounds. His time in Intelligence wired him into the old-boy network of bureaucrats who ran governments in Canada and Britain. In the late 1930s, they quietly assured him Britain and Canada would soon adopt the Bren gun, and someone could make a lot of money making those guns.

A factory would be needed and the John Inglis complex was in receivership and populated by three caretakers. Promising thousands of jobs, Hahn first drummed up political support. He leveraged this to line up financing, and bought the John Inglis Company in 1937. In March 1938, Hahn secured his first contract to make 5,000 Brens for Britain and another 7,000 for Canada.

The looming war justified skipping the formalities of competitive bidding … it was hoped. But memories of rotting boots and dead Canadians clutching jammed Ross rifles had been followed by years of depression, union-busting and exploitation. The average Canadian distrusted businessmen and high-handed government schemers.

The Canadian government dusted off the script from WWI and loudly declared there would be no tolerance for profiteering. A Royal Commission was formed to scrutinize the Bren contracts. “The Bren Gun Scandal” exploded, then deflated as the shooting war began. The Commission found no hard evidence of corruption, but the initial cost-plus pricing was rewritten to a management fee per gun to assuage critics. By the time the Bren production line started up in 1940, orders ballooned.

High Power production was more difficult than first thought. Reverse-engineering a gun is complex, and having original drawings of the High Power would shave many months off the schedule. Wisely, Saive and a handful of engineers had escaped the oncoming Nazis and fled to Britain. The British put them to work recreating the High Power drawings from memory, but Saive’s attention was divided: He was also working on what would become the SAFN 49.

Work was slow. The FN engineers believed the British intended to make the High Powers without compensating FN. This would not only rob FN of their share of profit at the time, it would flood the post-war market and destroy it for the future. The bad blood thickened when Inglis asked for the loan of the engineers and Britain refused. A plot was hatched to smuggle a set of original drawings out of FN. While the engineering dragged in Britain, the smuggled plans travelled seemingly by tortoise toward Spain. Both sets would be too late to be of use to Inglis.

By September 1943, Inglis’ tooling and production plans for the High Power were nearing completion. And, besides China’s order, the British Special Operations Executive was asking for samples.

The SOE was created by Winston Churchill to coordinate operations against the Nazis in occupied Europe. They wanted weapons to supply the underground. A quick fix was the provision of Lugers and Ballester-Rigauds in 9mm Parabellum. The High Power used the same ammunition and the SOE placed an order for 50,000 guns with Inglis.

This didn’t escape the notice of the Canadian Army and, on the strength of passing around Gen. Kiang’s personal gun, the leadership of the Canadian Army Overseas requested Inglis-made High Powers.

The SOE and the Canadian army did not want the shoulder stock and long range tangent sight beloved by the Chinese, so a second model of the Inglis High Power, the No. 2, was created. Except for the absence of a cut in the frame to take the stock, and the substitution of a fixed rear sight, the No. 2 was the same gun as the No. 1.

Duplication of serial numbers throughout the British Commonwealth was a problem avoided by the London War Office by assigning various gun factories blocks of numbers. This soon required constant monitoring and checking as more and more factories requested new blocks of numbers. The process was simplified by assigning letter codes to each factory. Normally, these were single letters, but the Chinese contract was an exception and assigned the code CH. This was followed by a four-digit serial number running from 1 to 9999. At that point, an additional numeral was added before the letter code, so the 10,000th gun of the Chinese contract would be marked 1CH0000 and so on. When the No. 2 assembly line began, the guns were assigned a T code, for Toronto, and the numbers counted up the same way.

In addition to the serial number on the frame, the same number appeared on the slide and the portion of the barrel visible through the ejection port. Thus most Inglis High Powers display their matching numbers in a stack of three.

There is no marking of No. 1 or No. 2 on any gun. The No. 1 is recognized by its tangent sight and shoulder stock, and the No. 2 by their absence. The large Chinese Mandarin markings on the left side of slide identifying the gun as “National Property of the Republic of China” were dropped from the No. 1 in May 1944.

Iron ore came by ship from north of Lake Superior. The mills near the harbor at Hamilton, Ontario, smelted it into steel. If you stood on the roof of one of the Inglis buildings at night, and looked southwest when the foundry doors were open, the red flare from 35 miles across Lake Ontario announced the eruptions of hot steel from the rollers. Hammered and rolled, the steel sparked and crackled and pinged to surly dark red, blues and purples. The rolls and plates then travelled, sometimes still warm, by rail to Toronto.

At Inglis, the High Power frames were rough cut from slabs of steel, eight at a time, by multiple cutting torches on “flame pantograph.” The slides were sawn from slabs and the barrels were machined from outsourced forgings. Then followed the grinding, milling, drilling, cutting, polishing, marking, fitting, finishing, assembly and testing.

As Inglis reverse-engineered the guns, they agreed to pay a royalty to Fabrique Nationale after the war. Out-maneuvered by their own greed, Britain let the Belgian engineers sail to Canada.

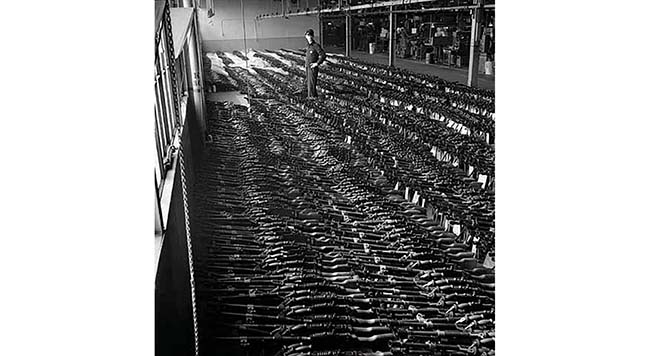

Inglis High Power production began in February 1944, with the first 500 guns slated for China. In March, 2,000 guns followed, and most went to the SOE. By September 1944, production leveled off at 20,000 a month.

There were some glitches. The Chinese FN-made guns copied by the Inglis engineers incorporated an outmoded barrel cam. This is the angled slot milled into the projecting piece of barrel below the chamber. As the slide moves back, a cross pin rides in this slot to pull the barrel downwards and unlock it from the slide. The slides then recoils and the world unfolds as it should. However, the squarish design of the early cut made the piece prone to cracking. A later, rounded design had cured this, a detail the Saive team reengineered in Toronto. Then, in tests of early production guns, it was found the ejector was too low and ejection erratic.

The new cam cut in the barrel was adopted and new barrels were issued for older guns as needed. The ejector was not so easy. The frame-mounted ejector slid through a machined slot in the slide, and the older slides were not cut deeply enough to accommodate the new higher ejector. It was necessary to mate the old and new ejectors correctly to the old and new slides. The taller ejector was designated the Mk 2 and marked with a 2 or II on one side. The slide with a deeper cut for the ejector was called the Mk 2 slide, but, it wasn’t stamped Mk 2. Instead, a gun incorporating both of these changes was marked as an Mk 1* on the slide. The Mk 1* modifications appear in both No. 1 and No. 2 models. Several minor changes that didn’t affect interchangeability were incorporated without identification.

The first 4,000 guns destined for China offloaded in Karachi, now in Pakistan, but part of India at the time. All war materials for China had to be flown north, at great cost in money and lives, over “the hump,” as the Himalayan barrier was called. Personal defense handguns were low on the priority list and, in the years since the 1941 Inglis order, America had equipped the Chinese with Colts in .45 ACP and the ammunition to go with them. The U.S. was less than eager to introduce a new caliber to the complex logistics system. Consequently, the first 4,000 High Powers sat in Karachi while thousands more piled up in Canadian warehouses from Quebec to Vancouver. To further confound matters, the Chinese Nationalist and Communist factions were both hoarding resources to fight one another. Fighting the Japanese was being left to the western allies and the Chinese order was being reconsidered by Ottawa.

The resulting rumors of cancellation made new orders paramount to Inglis. In wartime, mothballing a production line for possible reactivation was unheard of. If Inglis pistol production shut down, the machinery, tooling and floor space would be scavenged and devoured overnight and restarting production would be impossible.

But the Chinese contract was indeed cancelled. The large numbers of unassembled Chinese marked, and unmarked, frames and slides still in the production line were sent across the floor to build No. 2 pistols. The neat serial-numbering system went out the window.

Luckily, the Canadian Army Overseas did order the High Power just as the Chinese contract was cancelled. But, like the SOE, Canada wanted No. 2 Mk1*s. The No. 1’s stock didn’t improve accuracy, and worse, could tempt a careless user to put his eye directly in the path of the recoiling slide.

The No. 2 Mk1* was officially adopted by Canada in the summer of 1944. Britain followed with an order just before Christmas. Thousands of unshipped Chinese guns and parts, orphaned guns and mongrels filled out the orders. Soon, Canadian soldiers in Europe puzzled over their curious new guns firing German ammunition and decorated with large Mandarin characters.

The Inglis-made guns carried a variety of markings. All were marked “Browning FN 9mm HP Inglis Canada” and those accepted by Canada received a crossed-flag proof-mark stamp as well. Because the proof markings, and the Mandarin characters, were applied before the guns were finished and assembled, those marks are Parkerized. But, the serial numbers were cut later into the frame, slide and barrel after finishing and assembly to expose bright, raw steel. Many smaller parts, including the magazines, are stamped “JI” for John Inglis.

There are variations. Some guns earmarked for other than the Chinese sale or the various “T” numbered clients, were not marked as proofed or accepted. A dozen or so presentation models were chromed, gold-plated or Parkerized. Some guns were marked with serial numbers that did not include the “CH” or “T” letters and a number of completely unmarked guns went home with workers. Near the end of production, some were marked with Inglis’ diamond-shaped trademark. Just over 150,000 Inglis High Powers were finally produced.

At some time, likely in November 1944, the 100,000th slide made at Inglis was taken from the assembly line. The milestone No. 2 Mk1* slide was matched to a completely unmarked slotted frame originally made for a No. 1. Number 100,000 bears no acceptance or proof marks or serial numbers. Instead, the right side of the slide was somewhat unevenly roll-stamped before Parkerizing.

The 100,000TH

Canadian Automatic Pistol

Made By John Inglis Co. Limited

Toronto, Canada

The left side was marked later in different type, cut through the finish.

“PRESENTED TO H. J. CARMICHAEL”

The gun bears the Mk1* designation and a light Browning FN 9mm HP Inglis Canada. The tri-language “Canada” decals of the Mutual Aid Board affixed to most Inglis guns were fragile and soon worn away. It is unlikely 100,000 ever had one. There is no record of a ceremony like the one marking the assembly of Bren 100,000.

By the time 100,000 left the production line, Carmichael was planning the conversion of industry to peacetime requirements. At the end of 1945, he left Ottawa. C. D. Howe, the Minister of Munitions, commended Carmichael for performing “a truly outstanding war service to Canada.” He added that Carmichael even paid his own expenses.

Harry Carmichael didn’t smoke or drink, but he had one weakness … he loved horses. It’s said the only impulsive move of his life was to buy his first thoroughbreds over lunch. With those 14 horses, he opened his Garden City stable in St. Catherine’s, where he had begun his career in Canada.

Gen. Pia Kiang finally got his pistol back after it was hunted down and retrieved from a colonel who had quietly kept it as a memento.

Maj. Hahn continued to run Inglis. In 1954, he published his autobiography, For Action; the Autobiography of a Canadian Industrialist.

The Toronto Inglis plant is gone, the soot-blackened red bricks ground to dust and recycled. There is no Inglis Avenue, Bren Boulevard or High Power Lane. Today, any ghosts of Inglis drift through the tony condos, shops and parks of Liberty Village, the name being the only cryptic tribute to what happened there. It’s not really a bad trade; the working conditions in the drafty caverns would have been familiar to Dickens and Inglis survives today in such sleek modern plants as Whirlpool.

The Canadian government retains most of the Inglis pistols, and they remain the standard handgun of the Canadian Armed Forces. Canada is now shopping for a replacement. The Inglis High Powers will not enjoy an honorable retirement. When profane hands melt down the last High Power, a new Canada will have finally buried the Greatest Generation.

My mother, and her schoolmate, Maj. Hahn’s daughter Marion, remained lifelong friends. They have both passed on, but they visited frequently over the years, sipping tea and wine and the odd jug of Canadian rye whiskey. Marion brought her attractive niece along one afternoon. I was 15 or so when I showed Maj. Hahn’s granddaughter of the same age my bedroom.

For fear of litigation, and a black eye, I won’t mention her name. Like any good Canadian boy, I showed her my hockey stick and my guns. Maj. Hahn’s “force” was strong in that one. She was transfixed by my Sten Mk III gun and spent much of the visit cross-legged on my bed stripping and polishing it.

Lube? I croaked, offering a bottle of whale oil. Her smooth hands spread the emulsion over the bolt before she guided the steely cylinder into the receiver. Deftly snapping in the cocking piece, she fingered the trigger to let the bolt slam home to battery. About then, Mrs. Hahn and mom came to see how the kids were doing.

After bidding the guests goodbye, I returned to my room. My last pilfered cigarette was gone. The Sten was still smoking.

The author is indebted to R. Blake Stevens; the first Canadian writer to extensively document the FN and Inglis Hi Powers for Collector Grade Publications. Clive Law expertly expanded the study in The Inglis Diamond, also published by Collector Grade. Special thanks to Theo G. von Denta and Movie Armaments Group for editorial assistance. Photos from Libraries and Archives Canada, the Toronto Public Library and the late Lt. Geoff Winnington-Ball. The author has written numerous articles for Soldier of Fortune and Small Arms Review. His earlier books are available on Kindle. His upcoming book, The Right Gun, is a firearms guide for media professionals and will soon be available on Kindle.