By the summer of 1918 he was nearing his 65th birthday and might have been thinking about retirement, or at least slowing down. John had enjoyed an illustrious and profitable career in designing and building of firearms, and now faced a request that would be difficult to turn down. Fighter pilot and son of ex-president Theodore Roosevelt had just been shot down over France in a dogfight with an armored German aircraft. This tragedy further proved we were being outgunned in the air war. General Pershing, commander of the American Forces, had sent a message from England asking for a new .50 caliber round and two new machine guns; one for aircraft and the other for ground application. This was a time of war and American patriot, John M. Browning, would answer the call with his best effort.

For the operating system, Browning selected his famous short recoil cycle, deriving drive power from a recoiling barrel rather than porting the barrel for gun gas. This was a logical choice as the test gun from his earlier design, the .30 caliber Model 1917, fired over 39,000 rounds without a stoppage in acceptance testing. These new designs would be essentially scale-ups of the Model 1917.

Browning met most of his design objectives but there were two design challenges that he could not achieve. With the machine tools available at that time, the dimensions that established the location of the bolt face and the depth of the chamber could not be held tightly enough to control the fit of the cartridge in the chamber. This important dimension, known as headspace, can cause problems when out of specification. Depending on tolerances, the round could be too tight in the chamber, and the gun wouldn’t shoot at all. At the other extreme, the round was too loose in the chamber which resulted in a stoppage at best; or a ruptured cartridge at worst. The ruptured cartridge presented a serious danger to the shooter, spewing brass shards at high velocity out the bottom of the receiver. Another dimension that couldn’t be held close enough governed when the firing pin would fall – a dimension that later became known as timing.

Since these weapons had to be made on existing machinery, Browning made an easy adjustment that required the operator to screw the barrel into the barrel extension, moving the barrel toward the bolt face to reach the proper headspace. He developed a couple of simple gages that allowed the operator to adjust to the proper dimensions.

Weapon development proceeded rapidly, and then slowed after the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, bringing World War I to an end. Between 1923 and the ten years that followed, both aircraft and antiaircraft models were further refined with the new designation as the M2 for the aircraft model standardized in October of 1933 and the ground gun one month later. John M. Browning did not live to see this day, having passed away in 1926.

Only three years after standardization, the Spanish Civil War offered the M2 its first challenge. It was the ammunition, not the gun that was in question. The socialist Spanish Republicans supported by the Soviets and Mexico were in a civil war with the Nationalists who were supplied armament by Hitler and Mussolini. The war was heavily covered by the press and a proving ground for new armament. The Russian 20mm was quite effective as an aircraft weapon inspiring a reevaluation test against the M2. With its lighter, but still quite effective ammunition, testing in 1937 determined the M2 would be retained as an aircraft weapon. Military tacticians preferred the increased ammunition capacity of .50 caliber, even at the expense of a lightweight cartridge. Additionally, the high rate of fire of the aircraft M2 increased hit probability over slower firing larger caliber weapons.

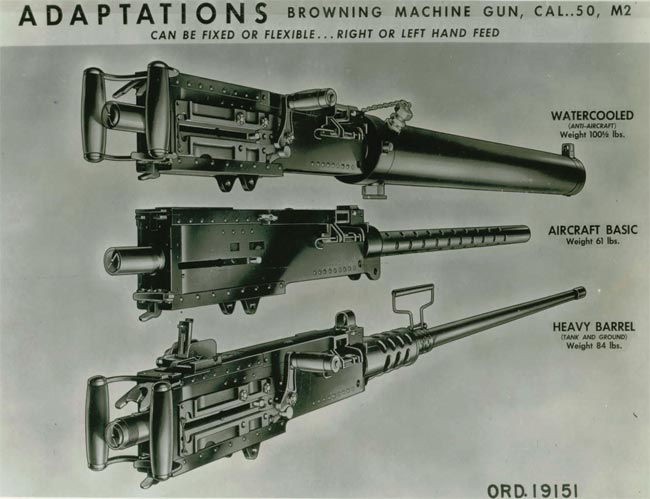

When the U.S. entered World War II, the M2 air and ground variants were quick to demonstrate their effectiveness. In anti-tank applications gunners would attack the tank treads whenever they encountered heavy tanks. The aircraft model was found on almost every aircraft in both fixed and flex applications. The Mitchell bomber, for example, carried fourteen. Ironically, even the Japanese were using the Browning, having purchased the design before declaring war, chambering the weapon for the 12.7 Breda cartridge.

As World War II ended, the military decided to look at some other gun designs. By now, modern manufacturing methods allowed most weapons to have fixed headspace and timing, yet there was one other major design drawback. The M2 wasn’t well suited to use in tank turrets. In designing a tank turret, it is important to keep access to the gun feeder from inside the turret so the gunner can load and unload from within. The M2 has a very long receiver, particularly the distance from the front of the feed location to the aft of the weapon.

At the war’s end, tanks had proven their battlefield effectiveness, evolving from vehicles that adapted existing weapons to a point where tank designs dictated dimensional constraints for new weapons. With a new main battle tank program on the horizon, the military had to get serious about finding a more suitable tank weapon. In the early 1950s they funded three different gun development projects to find a replacement. The days of the M2 appeared to be numbered.

The first of these was inspired by a large caliber German aircraft revolver cannon that looked like a promising approach so it was redesigned as a .50 caliber. Low reliability and an excessive amount of toxic gun gas introduced into the tank turret caused the design to be dropped. No matter. Two other designs were in the works. One was the T176, developed by Frigidaire and the other was the T175 by Aircraft Armament Incorporated (AAI.) Both had short receivers, fixed headspace and timing. Each had a new ammunition link that allowed the designers to shorten the receivers.

The receiver of the T175 was a full 7.5 inches shorter than the M2’s and that of the T176 was comparable. The M9 rearward stripping link, used with the M2, was a metallic link that had evolved from the cloth link belts used at the beginning of the century. Ammunition could only be drawn rearward for removal and was the principal cause for the M2’s long receiver. Frigidaire and AAI opted to develop a link as well as a weapon in order to meet the size constraints. Neither the T175 nor the T176 were developed in time for the Korean War so the M2HB and its aircraft variants, ANM2 and M3, was the heavy machine gun of choice, and performed admirably.

In 1958 it was time to end the dynasty of the M2. The new M60 tank was beginning development and its designers were promised a machine gun with a short receiver. Since the new weapon would require a new link and offer fixed headspace and timing, there would be no place for an old weapon with a World War I link? Besides, having the same ammunition on the same battlefield with two different and incompatible ammunition links was an unthinkable logistics nightmare.

The T175 AAI machine gun was further developed, designated the M85 and put into series production at Springfield Armory. It offered two rates of fire to meet both air and ground applications. The M85 was used on the M60 tank, but was not popular with tankers due to its unreliability. The M85 lacked control of the feeding rounds and problems with the rate reducer confined its use to the M60 and a few other vehicles.

Both the M2 and M85 were found in Vietnam though the tank of choice there, the old M48, still used the M2. After Vietnam, the General Electric Armament Systems Department, developers of the modern Gatling guns, proposed a unique approach to solve the tank gun problem. In 1978 they were awarded a design study contract for a .50 caliber externally powered weapon. Their GE-150 could use either link interchangeably and the gun fit in both the M60 tank and the new M1 tank, then in development. A cycling model was successfully built but a lack of funding killed the program.

In 1979 the U.S. Army launched its own design of a .50 caliber machine gun. The intent was to develop a .60 caliber weapon, but Picatinny Arsenal in Dover, NJ, decided they would make the first prototype in .50 caliber due to ammunition availability. The Dover Devil, as they called it, was lightweight, gas operated, and could feed from either of two incoming ammunition belts, giving the operator a choice between ammunition types.

The design was built and tested but the U.S. military decided against funding further development since by now the M2 had proven itself and there was plenty of ammunition in the field linked with the old M9 link. To keep the receiver short, the Dover Devil used the same link as the M85 but by now there was no longer much ammunition around that was linked that way. The Dover Devil may not have interested the U.S. Military, but a Singapore company was interested and by its own admission copied the design and completed development. It is now standard in the Singapore Army.

Without customer support, neither the GE-150 nor the Dover Devil proceeded past the prototype stage. For the new M1 tank, Chrysler would be obliged to make the commander’s cupola large enough to fit the M2.

As the 20th century came to a close, the M2 was now the only adjustable headspace weapon in the inventory. Reports of injuries from improperly headspaced weapons were on the rise. Three companies, Saco Defense, Ramo, and FN Herstal, all produced Quick Change Barrel (QCB) conversion kits that offered fixed headspace and timing for the M2. In 1997 the U.S. military held a QCB competition which was won by Saco Defense. Unfortunately, funding was lost before the design could be fully evaluated and the program ended.

Even though it required headspace and timing adjustments after barrel changes, the M2HB served in Desert Storm and performed with distinction, receiving huge accolades from the troops for its accuracy, reliability, and devastating firepower. Today in Iraq and Afghanistan the M2HB is one of, if not the top rated, machine gun in theater, yet, as expected, reports of field injuries from improper headspace adjustment continue. Frequent troop rotation has once again brought to light that setting headspace and timing is a perishable skill.

In 2007, the military found the money required for a Quick Change Barrel Kit and held a new competition. Saco Defense no longer existed, but won the competition again under the name of its new owner, General Dynamics (GD). The M2 with the QCB kit will be type classified early next year as the M2A1. The contract required that 30 kits be built and these are currently undergoing evaluation, with fielding expected for late 2010. As it nears its 100th birthday, the M2 will finally join the ranks of modern weapons with fixed headspace and timing. The M2 will be ready to last through another century. But will it survive?

For a number of years, GD has had another .50 caliber weapon in development. Borrowing design concepts from earlier work in developing a grenade machine gun, GD decided to adapt the concept to .50 caliber. The XM806 uses new lightweight materials and a unique impulse averaging operating cycle keeping its weight to a trim 40 pounds – less than half the weight of the M2. GD is also offering a new 14 pound tripod to accompany the XM806 that is half the weight of the standard M3 tripod.

At the end of 2009, GD will deliver twelve XM806 systems to the U.S. Government in support of a 450,000 round endurance and environmental test. Approval to enter production is expected in September, 2010 with low rate initial production expected to begin shortly thereafter.

Soon our old M2s will be upgraded so that the headspace and timing will be fixed, thereby resolving both safety and tactical issues. Next year, a new lightweight.50 caliber weapon, the XM806, will also be available to augment and perhaps one day replace the M2. Both of these weapons use the same M9 ammunition link, so there will not be a battlefield logistics issue.

All the moving parts seem to work together except that the M2 receiver is still too long to fit in compact vehicle turrets and the XM806 receiver is just as long. What about the tanks?